What is Atlantropa and why it failed

If Herman Sörgel, a German architect who lived between 1885 and 1952, had been listened to by the European leaders - and especially if Adolf Hitler and his allies had won the second world war, the African continent would have looked very different today.

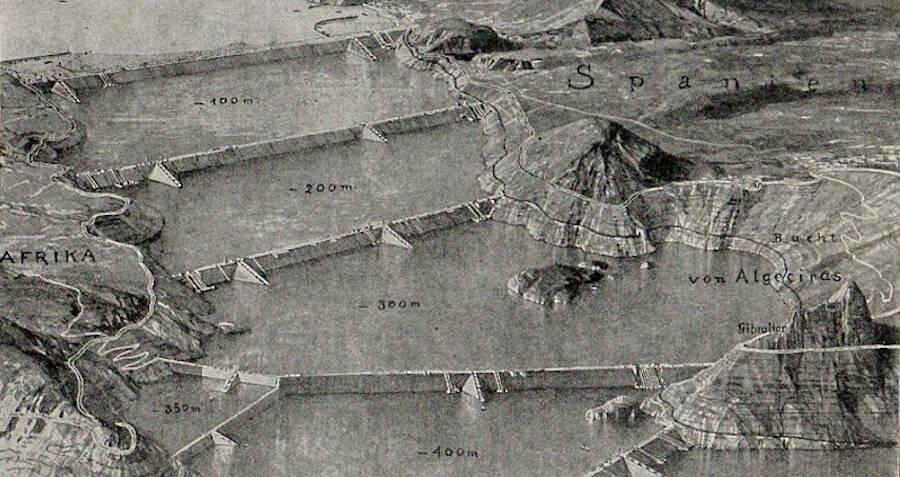

In the 1920s, Sörgel proposed an unusual project designed to close out the Mediterranean Sea with five hydroelectric dams and lower its surface to free new soil. In his opinion, the measure would solve the economic and political turmoil in Europe and link the old world with the African continent with land passages.

The architect believed that the dams should be built across the Strait of Gibraltar – in order to generate a gigantic amount of electricity and hold back the Atlantic Ocean, the Dardanelles/Bosphorus – in order to hold back the Black Sea, between southern Italy to Sicily and Tunisia – for a road corridor, on the Congo River – to irrigate the Sahara Desert, and at the Suez Canal – to lock the Red Sea.

A map of the Atlantropa project. Image: Wikipedia

New territories would be used for settlement and agriculture, he argued, pointing to the example of the Netherlands, most of which is below the level of the sea washing its shores.

Sörgel’s mega project was called Atlantropa, also known as Pantropa or Eurafrica. He was unable to answer just how much land his idea would have opened up, because no one really scanned the Mediterranean seabed at that time. The architect estimated the new areas between the two continents at hundreds of thousands of square kilometers.

Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Turkey, Yugoslavia, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt were to become larger countries and major beneficiaries of the project.

Sörgel’s vision was to unite Europe and Africa in a supercontinent to compete with North America and Asia economically and politically under four principles: pacifism, pan-European sentiment, Eurocentric attitude towards Africa, and – surprisingly – neocolonial geopolitics.

The latter basically envisaged a continued exploitation of the black continent, given that African peoples were still regarded as sub-human species.

Too big to digest

Herman Sörgel found way more critics for his project than supporters. Aside from a few architects, engineers and planners in Germany and northern European countries, no one seriously considered to close out the Mediterranean Sea and many laughed it off as utopia.

The proposed Gibraltar dam. Image: Allthatsinteresting.com

First, the World War I just ended and governments across the bankrupt European continent were struggling to push through recovery plans with limited resources. And Atlantropa wasn’t cheap at all.

Another reason is that participation in a common project of such magnitude was a novelty for the 20th century. There was no unity among the governments, some of which were preparing for a rematch rather than teaming up with yesterday’s foes.

Not least, the growing economy pie theory wasn’t valid at that time and capturing neighbors’ territories seemed more feasible, cheaper, and just.

Yet, Sörgel’s idea was pretty popular among planners in the late 1920s to the early 1930s, and between the late 1940s and the early 1950s. When the architect died in 1952, the project vanished.

What if?...

The German architect thought the European civilization would be able to solve its major problems by approaching to Africa. The new chunks of dry seabed would accommodate European settlers and businesses, give new farmland and an enormous volume of electricity, and serve as a bridge to colonize Africa effectively. Possession of territories in all climate zones was necessary for the sustainability of the future Euro-African entity, according to Sörgel.

Irrigation of the Sahara Desert from three man-made lakes in Africa was part of this plan. As climate should change, winters in Europe could be warmer, he defended the project.

One of the persons who liked the plan was Nazi Germany’s leader Adolf Hitler, who sew the sketches and whose dream of conquering the whole of Europe and colonize Africa coincided with Sörgel’s postulates, though for different reasons.

Herman Sörgel in 1950 or so. Family achives

After the second world war, western allies showed some interest in the Atlantropa project amid a growing sentiment of solidarity with African peoples and their struggle to earn independence from the Europeans.

There are debates among today’s historians whether Hitler would have pursued Sörgel’s project, if Germany had won the World War II.

Philip K. Dick, an American science fiction writer, fantasized on this topic in his dystopian novel “The Man in the High Castle”, empowering Reichminister Martin Heusmann, a chief Nazi engineer and acting chancellor after Hitler’s death, to work on a proposal to drain the entire Mediterranean Sea.

Whether a victorious Germany had succeeded in creating Atlantropa or anything of the kind we’ll never know, but we are all happy that it lost the war.

Sources: Xefer, Trove, CabinetMagazine, Wikipedia