Human ancestors were almost extinct 900,000 years ago

Before growing to more than 8 billion people as of early September 2023, the human population nearly perished some 900,000 years ago. More exactly, the number of Homo Sapiens ancestors in Africa reduced to a dramatic 1,280 individuals and didn’t expand again for another 117,000 years, according to a study published in the journal Science.

The work titled “Genomic inference of a severe human bottleneck during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition,” suggests that the loss of the population of ancestors to our species accounted for 98.7%.

The research, led by Haipeng Li, a population geneticist at the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, sheds light on a previously enigmatic period in our evolutionary history, primarily due to the limited fossil record from 950,000 to 650,000 years ago in Africa and Eurasia. Li suggests that this genetic bottleneck might explain the chronological gap in the fossil record during that time.

More to read:

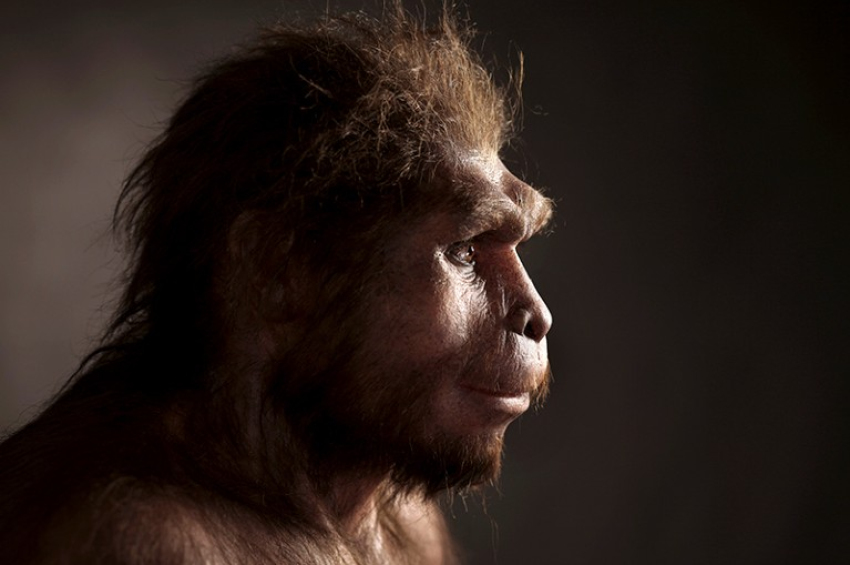

New clues why Neanderthals lost to modern humans

Nick Ashton, an archaeologist at the British Museum, expressed intrigue over the small size of the population. He told the magazine Nature that for such a group to survive, they likely inhabited a localized area with strong social cohesion.

What's even more astonishing is the extended duration of their survival, which implies the need for a stable environment with ample resources and minimal external stresses.

To uncover this historical population bottleneck, researchers had to develop innovative tools, including a methodology that allowed them to delve into the population dynamics of earlier human ancestors. By constructing a complex genealogical family tree, the team gained greater precision in identifying key evolutionary events.

“Population size history is essential for studying human evolution. However, ancient population size history during the Pleistocene is notoriously difficult to unravel. In this study, we developed a fast-infinitesimal time coalescent process (FitCoal) to circumvent this difficulty and calculated the composite likelihood for present-day human genomic sequences of 3154 individuals,” the authors explained.

Climate kills

This technique has illuminated the period between 800,000 and one million years ago, a time marked by the Early-Middle Pleistocene transition, characterized by profound climate changes and prolonged glacial cycles. Africa experienced extended droughts during this period, which might have contributed to the decline of human ancestors and the emergence of new human species. These newly evolved species could eventually have led to the last common ancestor shared by modern humans, Denisovans, and Neanderthals.

But around 813,000 years ago, the pre-human population began to rebound. The exact mechanisms that allowed our ancestors to endure and thrive during this challenging time remain uncertain.

More to read:

Why did our ancestors eat each other 1.45 million years ago?

Ziqian Hao, a population geneticist and co-author of the study, suggests that this bottleneck likely played a pivotal role in shaping human genetic diversity, including critical features such as brain size.

Given the vast number of archaeological sites outside Africa dating the period described in the study, some peer readers suggest the crisis leading to shrinking in the pre-human population was regional rather than global.

It is estimated that as much as two-thirds of genetic diversity was lost during this period. Perhaps, the lack of competition from other pre-human species, and abundance of flora and fauna gave our ancestors a boost in evolution after the crisis passed.