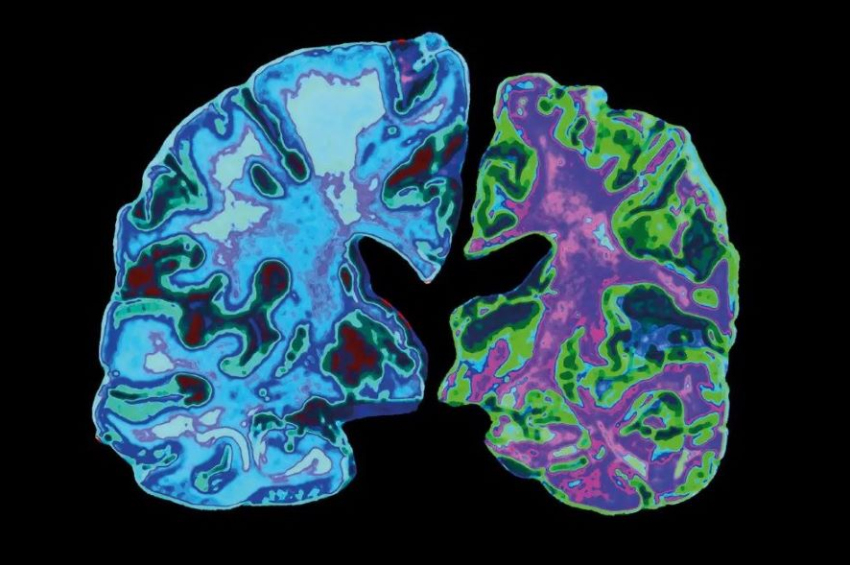

Alzheimer’s can be transmitted via bone marrow transplant

Researchers at the University of British Columbia in Canada have discovered that familial Alzheimer’s disease can be transmitted via bone marrow transplants. They arrived at this conclusion after performing lab experiments with mice and stem cells.

The study, published in the journal Stem Cell Reports, says that when bone marrow stem cells from mice carrying a hereditary form of Alzheimer’s were transplanted into healthy lab mice, the recipients developed Alzheimer’s disease at an accelerated rate.

This research underscores the role of amyloid originating outside the brain in Alzheimer’s disease, challenging the notion that Alzheimer’s is exclusively a brain disorder. Based on these findings, the researchers recommend screening donors of blood, tissue, organ, and stem cells for Alzheimer’s to prevent its inadvertent transmission through transfusions and cellular therapies.

More to read:

Study finds delicious food to be linked to Alzheimer’s disease

"This supports the idea that Alzheimer's is a systemic disease where amyloids expressed outside the brain contribute to central nervous system pathology. As we continue to explore this mechanism, Alzheimer’s disease may be the tip of the iceberg.

We need more rigorous controls and screening of donors used in blood, organ, and tissue transplants, as well as in human-derived stem cell or blood product transfers,” senior author and immunologist Wilfred Jefferies of the University of British Columbia was quoted as saying in a press release.

To test whether amyloid from peripheral sources could contribute to Alzheimer’s in the brain, researchers transplanted bone marrow containing stem cells from mice with a familial version of the disease into two strains of recipient mice: APP-knockout mice lacking the APP gene and mice with a normal APP gene.

Typically, mice with heritable Alzheimer’s begin developing plaques at 9 to 10 months old, with cognitive decline appearing at 11 to 12 months. However, transplant recipients exhibited cognitive decline much earlier—at 6 months post-transplant for APP-knockout mice and at 9 months for mice with a normal APP gene.

In mice, cognitive decline manifests as a lack of normal fear and memory loss. Both groups of recipient mice displayed clear molecular and cellular Alzheimer’s markers, including leaky blood-brain barriers and amyloid buildup in the brain.

The study concluded that the mutated gene in donor cells can cause the disease, as evidenced by disease transfer to APP-knockout mice without an APP gene and susceptibility of normal APP gene carriers. Since the transplanted hematopoietic stem cells can develop into blood and immune cells but not neurons, the presence of amyloid in the brains of APP-knockout mice definitively shows that Alzheimer’s can result from amyloid produced outside the central nervous system.

More to read:

High blood pressure may cause dementia, study says

The use of a human APP gene in the donor cells demonstrated that the mutated human gene could transmit the disease to a different species.

Future research will test whether transplanting tissues from normal mice to mice with familial Alzheimer’s could mitigate the disease, whether the disease is transferable through other types of transplants or transfusions, and whether cross-species disease transfer occurs.

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the W. Garfield Weston Foundation/Weston Brain Institute, the Centre for Blood Research, the University of British Columbia, the Austrian Academy of Science, and the Sullivan Urology Foundation at Vancouver General Hospital.

***

NewsCafe relies in its reporting on research papers that need to be cracked down to average understanding. Some even need to be paid for. Help us pay for science reports to get more interesting stories. Use PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu.