Japanese scientists discover signs of basic intelligence in obscure fungus

A team of researchers from Japan’s Tohoku University and Nagaoka College has made a surprising discovery while studying fungi: one of its species, called Phanerochaete velutina, is capable of a number of operations that you’d say are performed by organisms with brains.

During observations, they recorded that the P. velutina mycelium — which typically feeds on peach and nectarine trees — recognizes shapes and communicate information about its surroundings throughout its entire network.

"You'd be surprised at just how much fungi are capable of," the lead researcher, forest ecology associate professor Yu Fukasawa, was quoted as saying in a Tohoku University statement. "They have memories, they learn, and they can make decisions. Quite frankly, the differences in how they solve problems compared to humans is mind-blowing."

More to read:

Plastic-eating fungus found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

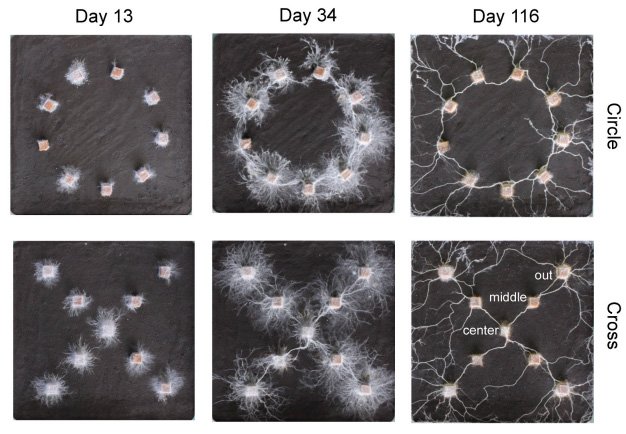

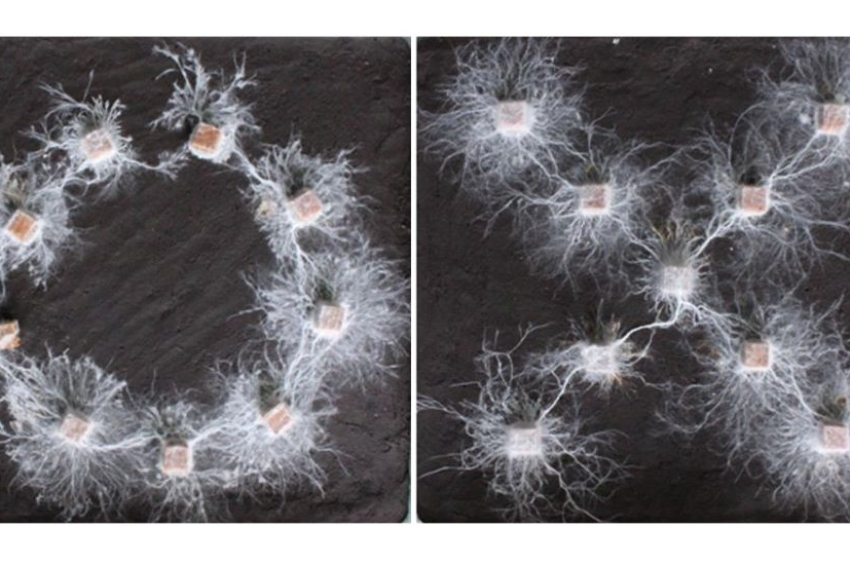

In a study detailed in the journal Fungal Ecology, Fukasawa and his colleagues arranged small wood blocks in different shapes, and allowed a network of P. velutina mycelium to populate them.

The experiments puzzled them: after learning about the environment, the mycelium appeared to be making decisions depending on the arrangement of the blocks, rather than simply spreading from a central point.

This evolution suggests a rudimentary level of intelligence, the researchers noted.

For example, when the blocks were placed in a cross pattern, the mycelium recognized the outermost blocks and appeared to communicate the arrangement back to the rest of the networking fungi.

More to read:

A species of fungus is capable of turning into carnivorous predator

But when the blocks were arranged in a circle, the mycelium never spread out into the center, suggesting it had figured out that no blocks existed there.

"These findings suggest that fungal mycelium can recognize the difference in the spatial arrangement of wood blocks as part of their wood decay activity," the paper reads.

The researchers explained that for the cross arrangement, the degree of connection was greater in the outermost four blocks, hypothesizing that this was because the outermost blocks can serve as "outposts" for the mycelial network to embark in foraging expeditions, therefore more dense connections were required.

In the circle arrangement, however, the degree of connection was the same at any given block. Since the dead center of the circle remained clear, they proposed that the mycelial network did not see a benefit in overextending itself in an already well-populated area.

“Our comprehension of the mysterious world of fungi is limited, especially when compared to our knowledge of plants and animals. This research will help us better understand how biotic ecosystems function and how different types of cognition evolved in organisms,” says the statement.

The researchers hope that their conclusions will boost advancements in other fields too, from studying other microscopic organisms such as slime molds, which have also demonstrated some sort of intelligence, to biological computers that are powered by organoid brain cultures.

"The functional significance of the fungal mycelia may provide insights into studying the primitive intelligence of brainless organisms, understanding its ecological impacts, and developing bio-based computers," the study concludes.

***

NewsCafe relies in its reporting on research papers that need to be cracked down to average understanding. Some even need to be paid for. Help us pay for science reports to get more interesting stories. Use PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu.

![[video] Aerospace startup proposes sled launch system to push planes into space](/news_img/2024/11/15/news0_mediu.jpg)