Chernobyl frogs adapted to high radiation exposure

The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster - one of the most catastrophic releases of radioactive material in human history – has left a lasting impact on the environment. However, new research indicates that wildlife in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, an isolated territory of some 2,600 square kilometers in northern Ukraine, has adapted remarkably well to high radiation.

A study in the Royal Society journal Biology Letters says that despite the high contamination levels of the past, present-day radiation levels appear insufficient to cause significant harm to the Eastern tree frog (Hyla orientalis) – which were the center piece of this study.

The international team behind this research focused between 2016 and 2018 on tree frogs across areas with varying radiation levels in the exclusion zone, looking for insights about the amphibians’ resilience.

More to read:

A new nuclear disaster is looming in eastern Ukraine

The researchers assessed frog populations for factors such as lifespan, stress hormone levels, and aging markers, concluding that the results showed no significant differences between frogs from highly contaminated areas and those from less affected regions. Current radiation levels were found to be below the threshold considered harmful to amphibians, suggesting that the frogs have maintained normal physiological conditions.

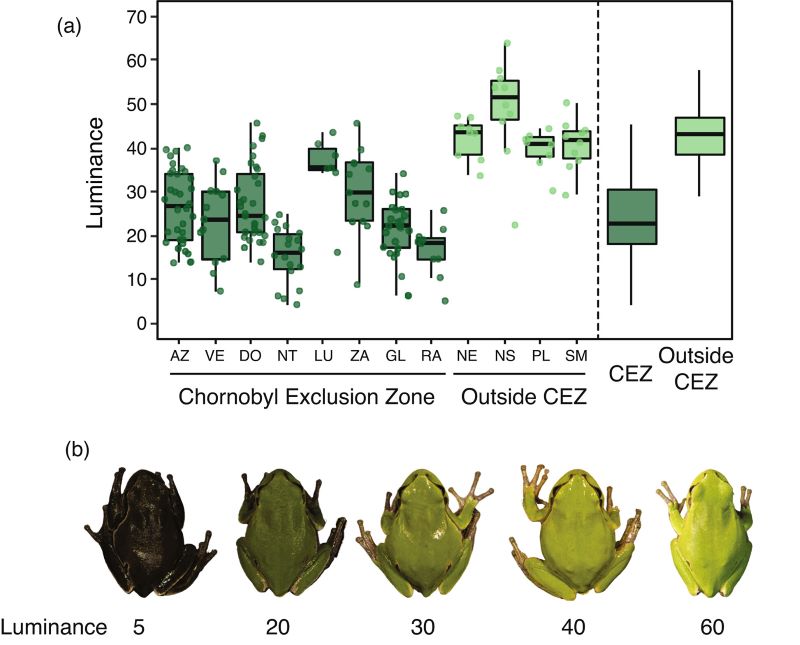

A fascinating aspect of this research is the frogs' apparent evolutionary adaptation. Previous research revealed that the 32-43 mm creatures in Chernobyl exhibited melanism, a dark pigmentation potentially linked to radiation protection. While the role of melanism in their survival today remains unclear, it may have been crucial immediately following the disaster when radiation levels were at their peak.

More to read:

As insect populations decrease, wildflowers started pollinating themselves

The study also highlighted that radiation exposure did not alter telomere length or aging rates among frogs. Mechanisms such as upregulated telomerase activity or antioxidant responses might explain this resilience, as observed in other species like bank voles in the same region. Similarly, chronic stress indicators, such as corticosterone levels, remained unaffected, even for frogs exposed to higher radiation doses.

Interestingly, frogs from areas with higher radiation were slightly younger on average than those from less contaminated sites, though this difference was not statistically significant.

The absence of human activity in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone has inadvertently created one of Europe’s largest wildlife reserves. Despite initial concerns, the region now supports a diverse array of species, including tree frogs, wild boars, and snakes, which appear to be thriving in the environment. This contrasts with earlier research on other organisms, such as rats and humans, where higher radiation doses were linked to health complications.

More to read:

Study: Humans have driven to extinction twice as many bird species as previously believed

Findings suggest that radiation levels in Chernobyl today are insufficient to cause chronic damage to amphibians like the Eastern tree frog. These results align with similar studies conducted in Fukushima, Japan, after its 2011 nuclear disaster. While current radiation appears manageable for wildlife, researchers emphasize the need for long-term studies to assess potential genetic effects.

As additional research is needed to assess the state of other lifeforms, continuation of scientific activity in northern Ukraine faces significant challenges due to the ongoing war with Russia, including infrastructure destruction and the presence of landmines.

***

NewsCafe is an independent outlet that cares about big issues.Our sources of income amount to ads and donations from readers. You can support us via PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu. We promise to reward this gesture with more captivating and important topics.

![[video] Trump just slapped penguins on Antarctic islands with tariffs](/news_img/2025/04/03/news0_mediu.jpg)