Earth used to have a ring like Saturn

Earth may have once sported its own ring system, similar to Saturn's, around 466 million years ago, which could have persisted for tens of millions of years, according to a study published in the Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

A team of researchers from Monash University in Australia suggest that the ring may have formed when a large asteroid crossed Earth's Roche limit — the point where the planet's gravity pulls apart a celestial body. As the asteroid disintegrated, its remnants were scattered along Earth's orbit, forming a ring, although likely less wide than Saturn's.

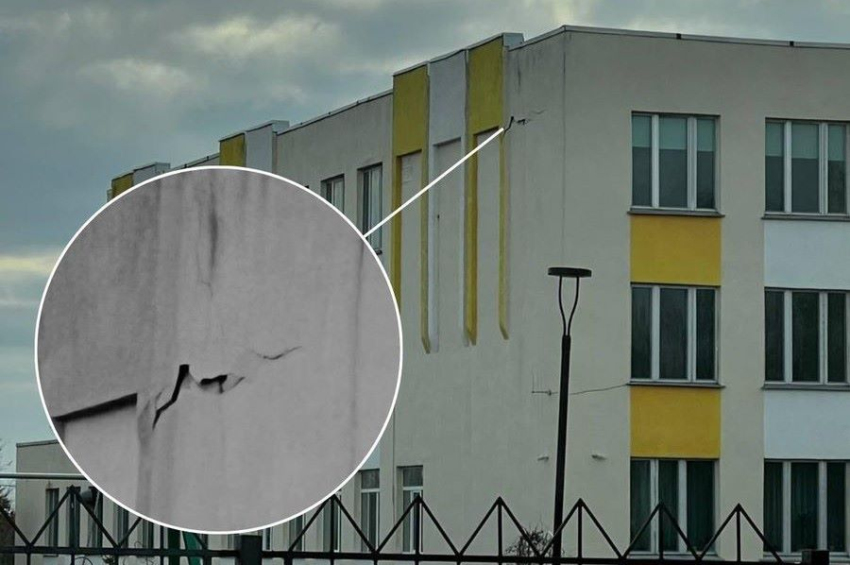

If this theory holds true, Earth still shows the aftermath of this ancient ring system: 21 meteor impact sites that fall within a concentrated zone near the equator, too precise to be mere coincidence.

More to read:

[video] A passing star altered Earth’s orbit 2.8 million years ago

This study not only provides a potential explanation for these craters but could also account for the Hirnantian Icehouse, a particularly cold period in Earth's history roughly 445 million years ago – which just brings more proof of the ring’s existence.

"The possibility that a ring system could have affected global temperatures adds a fascinating new layer to how extraterrestrial events may have shaped Earth's climate," says geologist Andy Tomkins, the lead author of the study.

The scientists first needed to prove that the craters weren’t randomly located. Using geological models, they accounted for tectonic plate movements to determine where these meteors would have struck millions of years ago.

They discovered that all of the impact sites were within 30 degrees of latitude from the equator.

More to read:

[video] An invisible electric field envelopes Earth, unknown until now

Next, they calculated how much land capable of preserving ancient meteor strikes was located near the equator at that time. This included regions in present-day Western Australia, Africa, North America, and parts of Europe. Remarkably, only 30% of the suitable landmass was near the equator, suggesting these impacts were not random.

"Typically, asteroids can hit anywhere on the planet, at any latitude, just as we see with craters on the Moon, Mars, and Mercury. […] It’s incredibly unlikely that all 21 craters from this time would be clustered near the equator if they weren’t connected. We would expect to see many impacts at higher latitudes as well," Tomkins went on in an interview with The Conversation.

More to read:

How much time is left before Saturn loses its rings?

The researchers propose that the ring would have cast a significant shadow over Earth, especially around the equator. This shade might have been enough to induce global cooling, helping to explain the timing of the planet's cooling around 465 million years ago, which was followed by the Hirnantian Icehouse 20 million years later.

While it is unclear how wide or dense the ring used to be, or how large the asteroid that broke up and dispersed in Earth’s atmosphere, the event nonetheless must have been a spectacular cosmic show.

***

NewsCafe relies in its reporting on research papers that need to be cracked down to average understanding. Some even need to be paid for. Help us pay for science reports to get more interesting stories. Use PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu.

![[video] Aerospace startup proposes sled launch system to push planes into space](/news_img/2024/11/15/news0_mediu.jpg)